By Kel Hahn

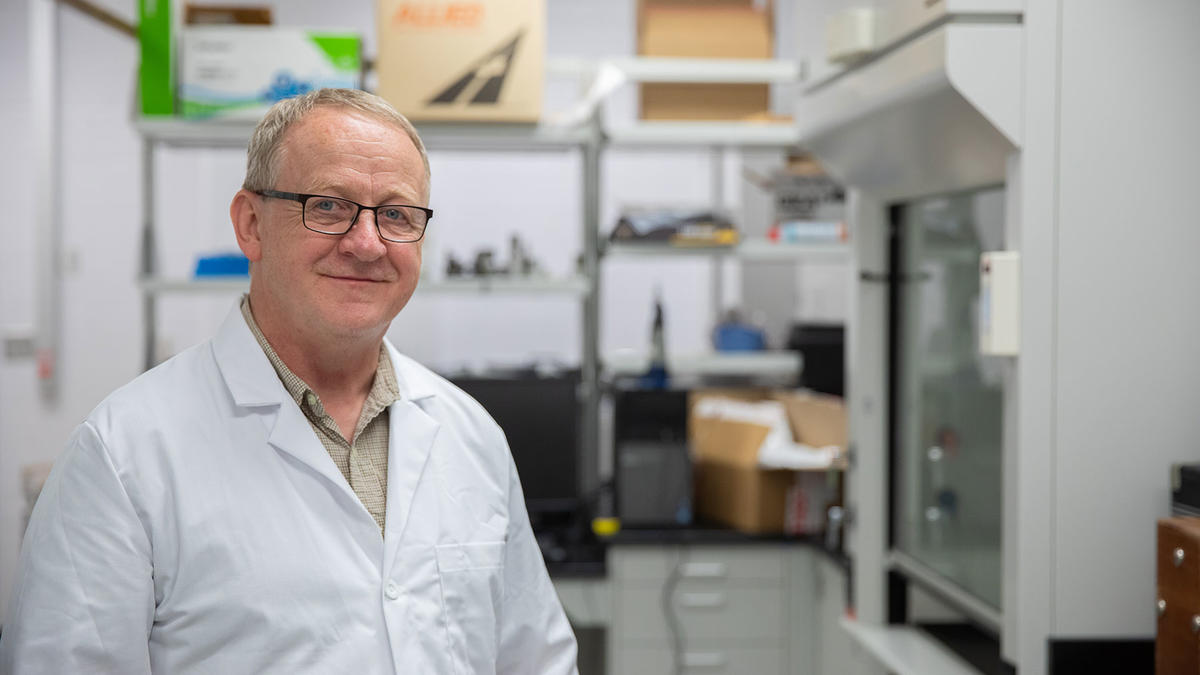

As former associate vice president for research at the University of Notre Dame, Suckow believed he could make significant contributions beyond his specific role as attending veterinarian. Cassis agreed. Today, Suckow is not only UK’s attending veterinarian, but also associate vice president for research and full professor in the F. Joseph Halcomb III, M.D. Department of Biomedical Engineering. Combined, his tripartite position allows Suckow to do what he does best: connect people.

“As an institutional veterinarian, I have a pretty good idea of the overall scope of work going on across campus. An investigator in engineering may be entirely unaware of what an investigator across campus is doing, and they need to meet because there’s potential synergy there. Several times in my career I’ve been able to connect people in meaningful ways, and that’s very satisfying.”

Born and educated in Wisconsin, Suckow did a postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Michigan before working at Purdue University, Notre Dame and the University of Minnesota over a 30-year span.

Clearly, he isn’t bothered by cold weather.

“Well, I’m used to it,” he chuckles. “The day my wife and I moved to Kentucky, it was -36 outside.”

What led to you veterinary medicine?

I came to veterinary medicine because it blended the two things I liked the most: animals and science. My mom didn’t feel I was responsible enough to have a dog for a pet, so I had other animals—mice, gerbils, frogs, everything. All of that helped develop my interest in veterinary medicine.

Do you have an area of specialization?

My specialty is comparative medicine and laboratory animal medicine. I’m specialty board certified in laboratory animal medicine. I work with mice, rats, rabbits—those kinds of animals. But I’ve worked with everything from fish to horses and cattle, raccoons, almost anything you can name.

What is comparative medicine?

Let’s say you have an idea for a drug or a treatment. First, you have to try it on something other than a person. That’s where comparative medicine comes in. Animals’ systems, anatomy and physiology have similarities to those of humans, so we can compare them. Where there are similarities, we can do modeling and understand more about human diseases and human physiology.

What discoveries have you made over the course of your career?

I’ve had the opportunity to work with some great people. Some chemists I knew had a compound in development, and I had the idea that this compound might have some application to diabetic wound healing—something they hadn’t thought about. I shared the idea, we conducted some experiments and together found that it did have a benefit for healing diabetic wounds, which is a huge problem. That work ended up becoming very well-funded, and intellectual property, as well as a company, resulted from it. Going from an initial idea, moving through pre-clinical animal models and then translating that into the clinic was extremely gratifying

I’ve worked with biomaterials of different kinds for wound healing and for hernia repair. I also worked with cancer models and developed intellectual property that’s now a product on the veterinary market for treating dogs with cancer.

Did you ever think about owning a private veterinary practice and seeing patients?

I thought about it a little, either having my own practice or maybe working for a large Wisconsin dairy farm. But I went the research route because I’m intrigued by the biology of animals. I love animals, but I was more interested in academia than private practice. In an academic environment, you always feel like anything can happen. Any minute, someone can walk through your door with a great idea.

You are UK’s attending veterinarian, associate vice president for research and a professor of biomedical engineering. What will the combination of these responsibilities look like?

Every day is different, and I’m figuring it out as I go. Many days I will have administrative responsibilities as attending veterinarian, but I also hope to have days where I’m teaching and instructing students in the research lab, as well as doing my own work and collaborating with other investigators whose work might be bettered by my veterinary experience.

How have you developed as a researcher?

I had a tremendous mentor at Notre Dame who was a veterinarian but worked as a cancer investigator. He had a rat model of prostate cancer, and he said, “If you want to work with this, it’s available to you.” So I worked in his lab, and he taught me things. That was really very formative for me in terms of becoming a researcher, even though I was well into my career at the time.

Once you master something, it’s easy to get complacent or lazy, but it’s fun to learn and do new things.

What do you like to do in your leisure time?

I like to go ice fishing, but that’s probably not going to happen a lot here. But I also like to go running and lift weights. I’ve heard that the UK Arboretum is a great place to run.

Did you ever get a dog?

Yes! We only have one now, a mixed breed named Rudy. But at times we’ve had as many as three.