By Kel Hahn

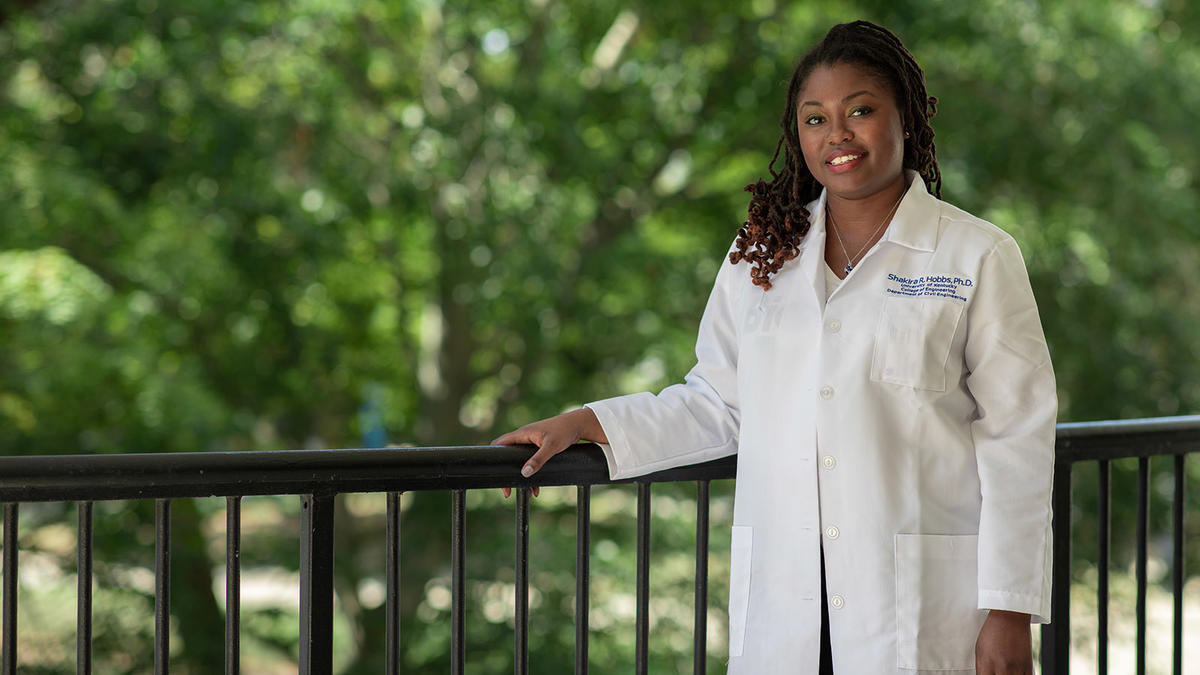

“Our department has a longstanding tradition of individual faculty members and students engaged in humanitarian engineering, but until now no one who fully specialized in that area," says Souleyrette. "Dr. Hobbs brings world-class education and experience in the science of humanitarian engineering. It’s fitting that she is developing and teaching our first dedicated course in this area, and we are excited for the students and teams under her leadership.”

Hobbs joined the Department of Civil Engineering faculty in February, and she has already published three peer-reviewed journal articles in just six months. Prior to arriving, she spent two years as a postdoctoral scholar in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at the University of Virginia. She earned her Ph.D. in civil engineering from Clemson University in 2017 and a master’s degree in engineering with an emphasis in environmental engineering from Arizona State University in 2014.

In this Q&A, Hobbs explains how humanitarian engineering is “engineering with the world in mind,” and how her own research within the food-water-energy nexus incorporates several disciplines within engineering, as well as the social sciences.

Your research works within the food-energy-water nexus. Can you describe what problems you’re trying to solve.

I look at ways to convert organic wastes, more specifically bioplastics and food waste, to energy. On the international side, I convert that food waste to energy for cooking fuel in a developing community in Belize. I also look at how agricultural runoff containing the herbicide glyphosate impacts human health.

But I should back up. In 2008, the National Academy of Engineers came up with 14 Grand Challenges for Engineering. The biggest thing we’re finding out about these initiatives is that we can no longer solve real-world problems in silos. We can't say, “This is environmental engineering,” or “I work on corrosion.” That kind of thinking doesn’t lead to collaborative solutions. So, while I work within the food-energy-water nexus, what we're finding is that food, energy and water are all connected and there are unique issues involved in each one of those.